My "horn heroes" - part

This third and final installment concerns my only "horn hero" that I had the privilege to meet, hear in live performance, and play for. Vitali Buyanovsky was already retired from the Leningrad Philharmonic in 1986 when he was going to be one of the featured artists at the Nordic Horn Workshop in Finland. I had heard rumors that gum disease prevented him from keeping the high-paced professional playing schedule that his position in the orchestra required. At this point I didn't know much about Buyanovsky except that he had been Frøydis's teacher and that he had written the four travel impressions for unaccompanied horn.

I signed up for a private lesson with him, but at 15 I didn't completely know how to take advantage of such an opportunity. What I remember most distinctly was his comment in broken German regarding the attack: "Die Zunge immer and die obene Lippe." (The tongue always at the upper lip - a slightly un-orthodox rule in retrospect, yet one that I find myself following most of the time...), and a probably somewhat exasperated complaint camouflaged as a compliment when he said it was impressive how I could reach the top of the range without any support whatsoever...

Buyanovsky played Rachmaninov's Vocalise with organ in one of the concerts at a local church. He wasn't visible from where I sat, but his sound was washing over me and even my cocky, uninformed 15-year old self knew I was experiencing something very special! I sat next to Frøydis at the concert and she told me later that Buyanovsky's own comment on the program was "Wer ist begrabt?" (Who is being buried?).

Buyanovsky seemed to me to be a gentle, warm soul. Somewhat old-school and formal. Well-dressed in a grey suit, and soft-spoken. (Of course most 50 somethings would seem old-school to a 15 year old...) I observed him in several master-classes and remember the quiet confidence he exuded. One of the great young Finnish players (can't remember if it was Markus Maskunitty or Esa Tapani...) played the Weber Concertino for him, and Buyanovsky needed artistic cohesion and structural logic - strict tempo through all variations... The Danish player Nina Jeppesen played Gliere for him - she studied with Frøydis at the time and he was more animated than normal. Maybe he made some comment about how not many girls - besides Frøydis, and now Nina - could play this piece?

The next time I met Buyanovsky, I was a better player - already semi-professional - and quite a bit more aware. Frøydis' horn class went to Gothenburg in the spring of 1990 for a long-weekend of master-classes, horn ensembles, concerts and the typical horn geekiness that follows. I played Buyanovsky's 1st solo sonata for him and he seemed pleased - not making many obvious suggestions but rather singing along and making encouraging gestures. When I couldn't make the chords at the end of the 1st movement work out, he wrote in an optional ending with single notes. He did pick up his horn to play, even though this was apparently very rare at this time. He played a three octave scale with no pressure at all - shimmering, yet full and ringing sound, and said this was proof that one really didn't need to practice!

The most memorable moment of the weekend for me was when Buyanovsky stated "Das Ideal für Horn spielen muß immer die Gesangstimme sein." (The ideal for playing the horn must always be the human voice.) Someone from the audience asked: "But Mr. Buyanovsky, how about Shostakovich?" - obviously referring to the composer's more percussive and aggressive writing. Buyanovsky looked at him with a very sad face and started singing in the most gentle way the lyrical solo from the finale of the fifth symphony.

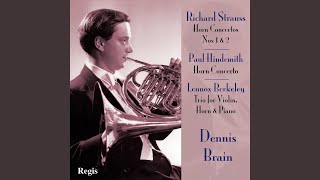

I did feel that I had met one of the greatest horn-players of our time and a genuine artist, and he made a very strong impression on me after these two rather superficial meetings. It was only a few years later, however, that I really started exploring his recordings and got to know more about his work. Frøydis introduced me to his recording of Tchaikovsky's symphonies (I believe there are three versions with Mravinsky conducting - she recommended the one from 1960). Buyanovsky plays the solo with such freedom of sound, the most fluid legato and with clarity of phrasing that comes from fully owning the music. I started searching out Mravinsky recordings of works that feature the horn and was never disappointed: although the orchestra sometimes has some rough edges for today's ears, the interpretations were always powerful and the players totally committed. Buyanovsky played with poise and lyrical power and that warm, singing sound that just had limitless potential. I found that he had recorded most of the solo repertoire as well, but the only items I could locate were live concert recordings of Mozart 3 and Strauss 1, as the old Melodiya LP's hadn't been transferred to digital mediums.

How happy I was to see this change with the release of four CD's highlighting his recording career! (I've included a link for those who are interested in hearing for themselves his remarkable artistry.)

The Soviet Union was in so many ways a world apart and in the last century there would still be significant geographical variations in instrumental styles. Buyanovsky's horn playing represents the very finest in a style that doesn't really exist anymore - his heirs in Russia don't use the same vibrato and aren't always wearing their hearts on their sleeves as Buyanovsky seemed to do. Some of us will have a hard time enjoying the artistry of someone playing our instrument within a different tradition than our own, but to me this is some of the finest horn playing ever caught on tape: Buyanovsky performing Rossini's Prelude, Theme and Variations.

P.S. One last story that Frøydis shared with me which remains very vivid to this date: A young Buyanovsky is walking on the street in Leningrad when a man stops him and asks if he is not the horn player at the theatre. Buyanovsky answers in the affirmative and is then complimented effusively on his beautiful solo last night. Buyanovsky thanks the man, but is secretly puzzled as he can't remember having any solos from last night's Verdi opera. When he gets back to the pit, he flips through the entire part to see what solo the man was referring to in such glowing terms. He finds one note that he holds out by himself - that must be it! And that is the power of our instrument in the hands of an artist such as Buyanovsky: To play that one note in such a way that it changes the life of a random listener! D.S.